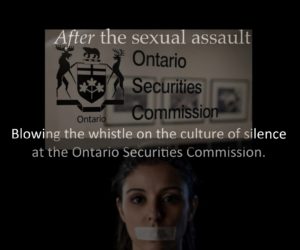

Earlier in my previous — and since demolished— career, I was sexually assaulted by the powerful head of a major Canadian securities commission. It occurred in the dark of night at an out-of-town conference I was required to attend as part of my job with the Ontario Securities Commission. The sense of being violated, degraded and humiliated was overwhelming. The combination of fear and anger was unlike anything I had ever felt. I had no idea it was about to get worse, and for a very long time.

In time, the bruises from the assault faded. The bleeding head injury eventually healed. The consequences to my dignity, peace of mind and livelihood never have. But it is the betrayal by those I trusted to protect me — beginning with a boss who bullied me, Harvey Weinstein style, into staying silent about being attacked, then my former employer, the OSC, which treated me like I was the offender when I reached out more recently, and finally, Ontario Premier Doug Ford, who turned a blind eye and enabled efforts to muzzle me again — that has caused the deepest trauma. This is a premier who has said he will protect women who come forward in this #MeToo era with his life. I feel like he took a wrecking ball to mine.

The life-altering after-effects of this unending nightmare are not episodic. They are every day.

I never wanted to speak publicly about being sexually assaulted. No victim should ever be forced to. It would not have been necessary if those I relied on, including the premier of Canada’s largest province and the Ontario Securities Commission — a public institution that regulates the conduct of others — actually did the right thing. Instead, they left me to twist slowly in the winds of indifference and disrespect.

I have often said that sexual misconduct is hazardous to the workplace, and to a woman’s health especially. Sexual assault and sexual harassment can produce a host of debilitating, even life-threatening, emotional and physical sequelae, from sleep disturbances and depression to PTSD and cardiovascular disease.

In some cases — more than the media ever report — they have had a tragically fatal outcome.

Yet, by their frequently insensitive and often malicious mishandling of claims of sexual violence — a propensity to respond with accusatory lawyers, rigged investigations and the failure to provide true victim-focused support — too many institutions inflict what amounts to a second assault on the victim. The harm they cause in doing so can even be worse than the damage inflicted by original incident.

I learned recently of a serious adverse turn in my health, which my doctors tell me has been caused by my exposure to the toxic waves of retraumatizing events of the past year. When I came forward to the OSC, even in a time of #MeToo awakening, I was still not believed. I was not supported. I was blamed and again made to feel that I was the offender. It was just like it was years ago, when I reported being sexually assaulted to a boss who responded by threatening my job. In trying to find healing, all I found was harm.

Instead of protecting me, or addressing the concerns I raised about the possibility that there were other victims whose complaints were mishandled by my former employer, this premier enabled the OSC to try to silence me again. Together, Premier Ford and the OSC have brought back to life the worst memories of the painful past. It was as if they intentionally set out to inflict more harm on me. I felt like I was being assaulted all over again. If you needed an everyday workplace definition of institutional betrayal, this would be it.

When Mr. Ford, and his controversial chief of staff, Dean French, repeatedly ignored my follow-up, it was all the proof I needed that muzzling me was exactly the outcome the Premier had in mind.

I know this is the same premier who dismissed as “just a bunch of nonsense” allegations of sexual misconduct against his finance minister, Vic Fedeli. But I can’t describe the sense of utter betrayal I felt then, and still do, because he did not think I was even worth the courtesy of a response, much less an effort to sincerely deal with my concerns in a victim-focused manner.

I had been sexually assaulted by one powerful man and bullied by another into keeping quiet about it. Now the most powerful political figure in Ontario seemed determined to leave his footprint on my life as well.

Let’s be clear: it is the failure to respect women that is the telling genetic marker of sexual violence. It is what lies at the core of every act of sexual assault, every incident of sexual harassment, every decision to engage in retaliation, and every choice to turn a blind eye to wrongdoing. If we want to get to zero tolerance for sexual misconduct, as Premier Ford claims, we need to have zero tolerance for disrespecting its victims. It appears that some powerful men still have to learn that lesson, and sometimes in a very public way.

Elizabeth Renzetti was right when she warned that we need to be concerned about the way women are responded to when we come forward. As it is now, most cases of sexual violence are never formally reported. If we believe coming forward will leave us worse off, as it has me, women will forever be forced to live in the shadows of fear and injustice. And we will never be equal in the workplace or anywhere else.

One of the transformative messages of #MeToo is that it is through the personal narrative — the willingness of victims to stand up and blow the whistle on powerful predators, enabling actors and miscreant organizations — that real change is effected. Personal stories matter. As an early whistleblower herself, Ida B. Wells once said, the “way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

I hope my story can begin to do that— especially for all the victims who are desperately hoping to move out from the shadows and back into the light of a fulfilling life.

Learn about how the OSC thinks whistleblowing is good for everyone — except when it involves the OSC.

how the OSC thinks whistleblowing is good for everyone — except when it involves the OSC.