- Home

- Ottawa Needs to Drop the “Scarlet Letter” Provision in its Sexual Harassment Bill

Ottawa Needs to Drop the “Scarlet Letter” Provision in its Sexual Harassment Bill

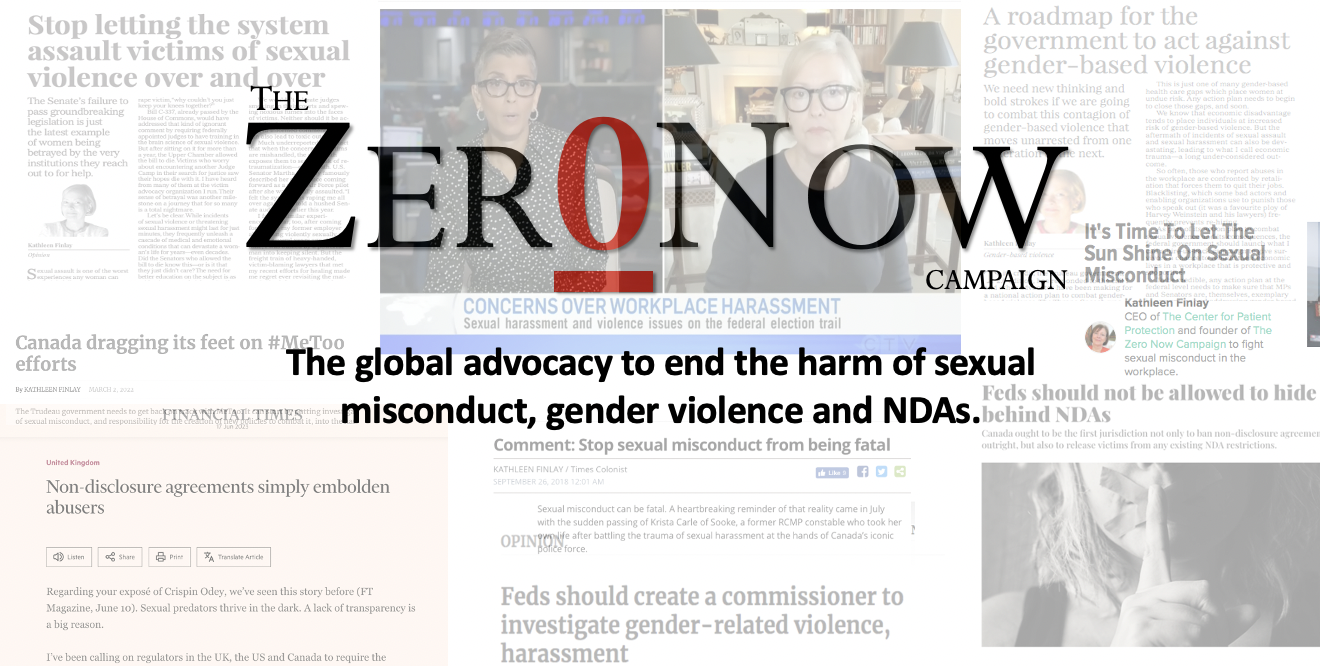

“When women speak up, we have a responsibility to listen to them and to believe them.” Many advocates have argued that in the past, but only one prime minister has boldly declared it as a matter of his government’s policy. To countless women across Canada, Justin Trudeau’s statement was seen as a turning point that was long overdue. The fear of not being believed has been a prominent factor in why so many women have been reluctant to report sexual misconduct. I hear the tragic stories of these women, and other survivors, every day at The Zero Now Campaign I founded.

Oddly, his government’s flagship legislation dealing with sexual harassment and violence in federally regulated workplaces sends the exact opposite message from the one conveyed by the Prime Minister. The proposed legislation, known as Bill C-65, contains a provision that would allow the minister overseeing the law to refuse to investigate any complaint about sexual harassment or violence if the minister is of the opinion that it is “trivial, frivolous or vexatious.”

Seriously?

The “vexatious” provision loudly portrays women as possible mischief-makers in raising sexual misconduct claims, when available evidence is precisely contrary to that notion.

This is a terribly counterproductive move, and one that could well place more women at risk because they will be reluctant to come forward. It is reminiscent of the days when victims found themselves confronted by the slut or nut attack after they complained about sexual misconduct. It is totally at odds with the principle that we should be respected and believed. The “vexatious” provision loudly portrays women as possible mischief-makers in raising sexual misconduct claims, when available evidence is precisely contrary to that notion. In doing so, it perpetuates a false stereotype that has no place, and no factual justification, in the 21st century.

While there is no credible factual support for the proposition that women file trivial complaints in any significant numbers, there is authoritative research, as well as compelling anecdotal evidence, to confirm we have been treated in a trivial fashion by organizations, including government and public sector entities, when we have come forward. This is in addition to the vexatious spirit of retaliation that organizations commonly adopt in the aftermath of sexual misconduct complaints.

Too many of us who have come forward have found ourselves in that boat, and too many of us have had our lives and careers capsized by the swells of retaliation that surround us.

Anything that might be construed as a message to women that, if we make a complaint, there is a risk of being subjected to yet further humiliations and attacks on our character, must be scrupulously avoided by governments at every level, especially when research shows that 99 percent of all sexual harassment claims are legitimate.

The same cannot be said for investigations into sexual harassment claims.

Just this week, for instance, court records disclosed that in cases involving gender discrimination complaints at giant Microsoft (including sexual harassment), the company’s internal investigations went against the individual making the complaint in 99 cases out of 100. These kinds of statistics reveal a lot about whether or not organizations take sexual misconduct seriously, and they are another reason why we need a sunshine law, as I proposed earlier on this site and in my submission to the House of Commons.

It is not uncommon for women to experience waves of emotional and physical harm following sexual misconduct incidents. These waves can last for years. The aftermath of filing a sexual misconduct complaint, especially when it is mishandled, is not unlike the traumatic emotional impact of medical errors on patients and families. Research has documented that there can be long-term consequences to a victim’s health, with depression, PTSD, anxiety, heart disease, sleep disorders and thoughts of self-harm being prominent among them.

“I lost my job, my marriage, my reputation, my income and my home.”

Less noted or understood are the financial costs, which can be devastating. In the everyday workplace — where women cope with reality without red carpets, designer black dresses or the supporting scrutiny of big media — the typical outcome is still I-had-to-leave-but-my-harasser-stayed. Many survivors are never able to resume a career in their chosen field. Others have to quit their jobs and, in effect, start from scratch — and that’s if they can find meaningful work at all.

Few women have summed up the nightmare of these consequences more graphically than one who reached out to me. “I lost my job, my marriage, my reputation, my income and my home,” she said. “My work colleagues didn’t want to have anything to do with me anymore. I was a pariah to them. I lost everything and I thought many, many times about taking my own life, especially when I saw my harasser continue to thrive in the organization that was more than happy to assassinate my character and then throw me under the bus.”

That nightmare can’t be allowed to happen to any other woman. Ever.

There’s only one person who can change the terribly regressive direction this bill is taking. That’s the Prime Minister himself.

I fear, though, that this is precisely what the “vexatious” clause, and the mindset that permitted it, foreshadow.

Such terms as “trivial, frivolous and vexatious” harken back to another time of gender-degrading epithets. It’s just a modern way of being able to slap a big scarlet letter on a woman and brand her as a troublemaker, as someone who can’t be trusted or believed.

Is that really the federal government’s takeaway from the avalanche of scandals and headlines that show how pervasive sexual misconduct in the workplace is and how damaging it can be to women?

If the government is serious about combating sexual misconduct in its ranks, it needs to get rid of the “vexatious” provision entirely.

Right now, there’s only one person who can change the terribly regressive direction this bill is taking. That’s the Prime Minister himself.

If this is really a time of “awakening” when it comes to combating sexual misconduct, as Mr. Trudeau has wisely observed, the content of his government’s legislation needs to reflect that reality — not threaten a throwback to a much discredited past that harmed too many women.